Unimog 437

August 19, 2018 5 Comments

If my previous builds are any indication, I am a big fan of Unimogs. So it was just a matter of time before I built another one. Rather than building one this time, I built a modular system that allows for a number of different versions.

Full instructions can be found here.

This build started with a desired to make another small build with the great Fischertechnik tires I acquired. I wanted to build something small and playful like RM8s FJ or Sheepo’s Defender. As has been happening with many of my recent builds, I wanted to give the MOC some playable options and easy modifications. A Unimog was a perfect option, and who am I to turn down a Unimog? So I gave myself the following constraints: 4×4, I4 fake engine, steering, manual and PF drive options, removable cabs, removable bed, and two chassis. I set off to work.

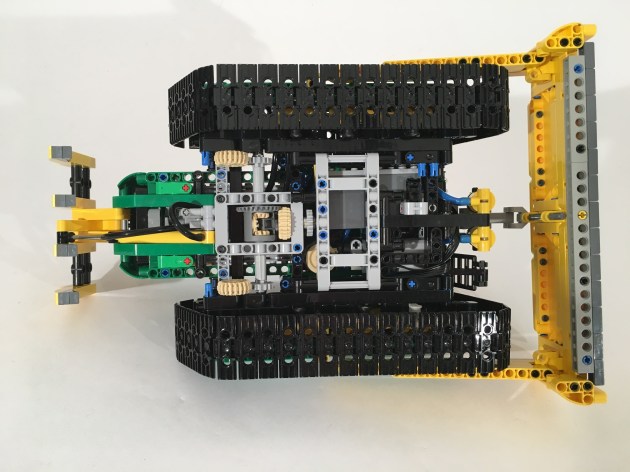

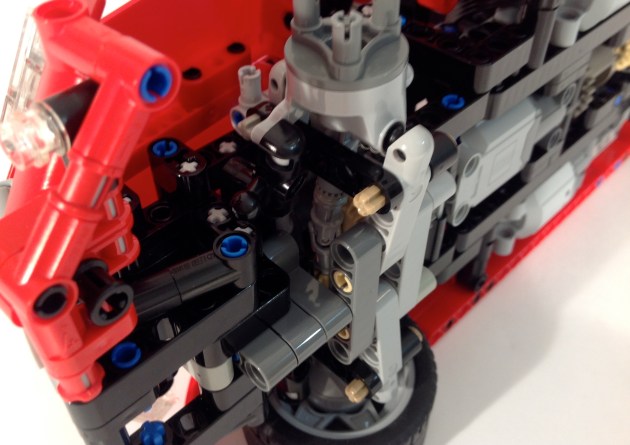

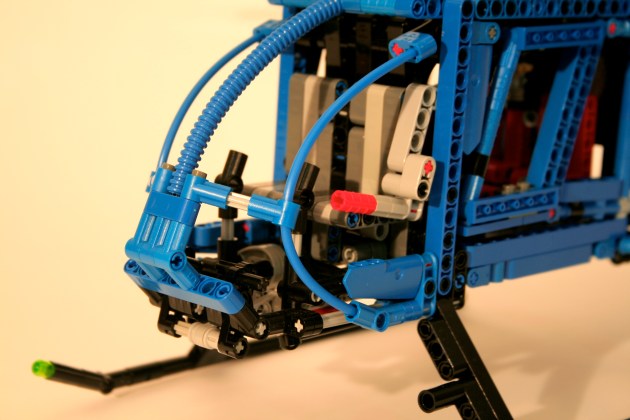

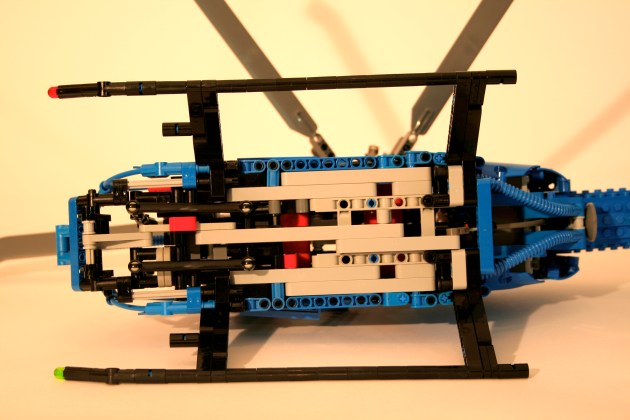

The axles came together fairly quickly. I decided quickly not to do portal axles, because I wanted the complexity of the MOC to be elsewhere. Both axles have a differential, two soft springs, and are stabilized longitudinally via steering links and laterally via panhard links. All for shocks are mounted on crankshaft parts to get the ride height of the Unimog just right. There is about 1.5 studs of travel for each wheel, which provides adequate articulation.

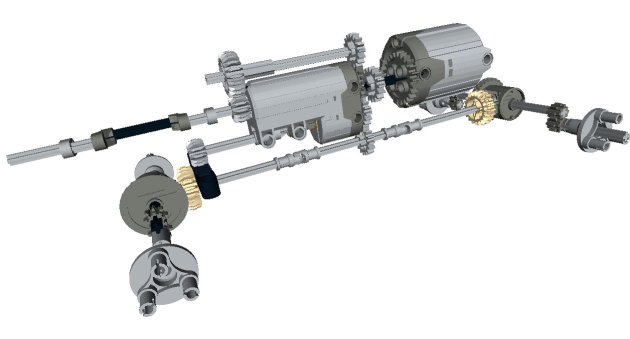

The axles are connected to a fixed axle that powers a I4 fake motor. Since I wanted the MOC to be easily switched between manual control and PF, the driveline got a little over-complicated quickly. The steering axle and drive axles cross each other twice. This allows for the steering to go to the top for a HOG, and backwards so a PF servo motor can be added. A 16t gear is available at the top of the chassis to power a PTO, or add a PF XL motor to give the Unimog propulsion. The long Chassis can fit a full a full Power Functions pack. When the power pack is not installed lots of open space is available for other additions. I added a three way tipper lift mechanism for both the long and short wheelbase chassis.

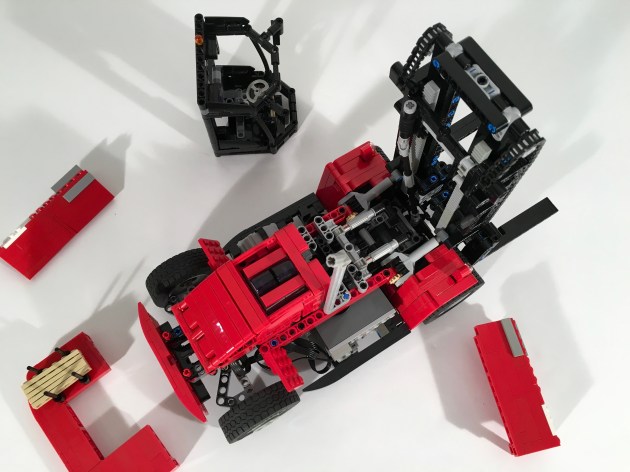

Attachment points were added for the rear bed and for the cab. I created three cabs, and each can be added to both chassis (though the Doka looks best on the LWB). Two axles with stop can be pulled to free the cab. I created three beds and a power pack. Four axles with stop are required at each corner to secure the bed. A camper and a crane bed are not far behind on my building queue.

The Unimog turned out exactly as I wanted. The suspension and steering are light and smooth under manual operation, and work great with PF. I am excited about the ability to offer and develop multiple beds and cabs. Instructions are posted, so I look forward to seeing other options people develop to make their own Unimog.

- Unimog 437